With the Presidential campaign now seemingly in full swing and hundreds of Senate, Congressional, Gubernatorial and local races beginning to ramp up, the air waves will soon be inundated with political advertisements by candidates, interest groups and political action committees all jockeying to have their candidate be the last one standing when the dust settles. It seems that during every election cycle we hear stories about the bitter nature of campaigns today and how, despite a strong and growing public opposition to negative ads, they will play an integral role in the race for whichever office is most hotly contested. Being a bit of a political junkie myself, I often have friends, family and co-workers ask me why do these campaigns feel so compelled to go negative and when did all this negative campaigning start? So as a precursor to the coming onslaught of political advertisements coming soon to a television near all of us, I thought I’d provide some insight on these types of ads both from a historical and advertising perspective.

When did it start?

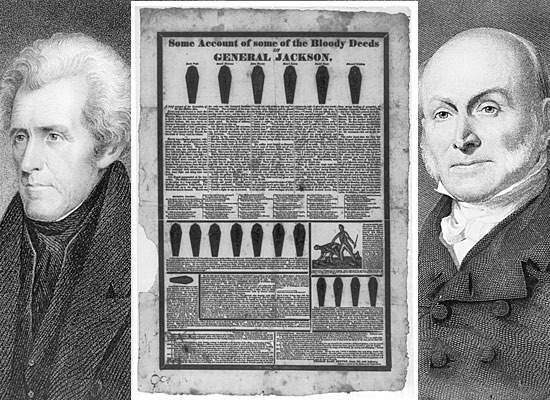

The political equivalent to a “low-blow” is nothing new as you can see by the headline of this campaign literature attacking then General Jackson about some of the military tactics he employed. Or the attempted character attacks on President Woodrow Wilson who, while in office, met a woman named Edith Gault then proceeded to date her and marry her all while attempting to form a League of Nations. Regardless of the many examples throughout history of political mudslinging, we typically think of negative political ads as an invention of the last 50 years, with increasing frequency and bite with each election cycle.

Focusing in on only those negative ads that were spring boarded to prominence through the use of television, we can clearly point to the campaign to re-elect President Lyndon B. Johnson as the father of negative ads as we know them today.

After watching this ad there’s no doubt that a powerful message is being sent but, in terms of a personal attack, it’s a far cry from others we’ve seen throughout the years. For example, the infamous “Willie Horton” ads created by the presidential campaign for then Vice President George H.W. Bush (who just turned 88 years old this week). The “Willie Horton” ads were exceptionally brutal and relied heavily on the incredibly strong emotion of fear to motivate voters to vote for then Vice President Bush if they had an interest in preserving peace and safety in their communities.

Since the “Willie Horton” ads, we’ve seen countless others from both political parties in every election cycle all negative and most attempting to call on some innate fear shared by many in the electorate that will motivate them to vote, vote for someone else or sometimes not vote at all.

Why the negativity?

The natural question surrounding political ads is why must they all be so negative? There are numerous motivating emotions that companies and organizations use to promote their products and services with great success. So, why do political campaigns seem to avoid these other alternatives and turn directly to smear tactics? You don’t see a McDonald’s ad bashing the food and safety standards used by Burger King or a Target ad throwing stones at Walmart. So what is the difference when it comes to politics?

The answer to this question is simple yet understandably difficult to grasp at first. Political campaigns, unlike product campaigns, are tasked with promoting, and in essence, selling an individual to a population hard wired to question their elected officials and those seeking public office. This distinction is significant, because when promoting a brand of soda or a fast food chain, the advertising can focus in on taste, value, convenience and any number of motivators that lead to a decision to purchase their product as opposed to a competitor’s product with miniscule ramifications for that decision. Alternatively, when attempting to promote the intelligence and moral character of an individual that is trying to make their case for becoming the next leader of the free world, holding nuclear launch codes and having a direct impact on how much money is taken from your paycheck, the stakes are much higher.

In this sort of high stakes ad war, taste, value and convenience are entirely insignificant. Therefore, campaigns are forced to rely on the most powerful and also most dangerous emotions of fear and excitement to sell their candidate as the right choice. And because of the gravity of the decision at play, excitement is teamed with caveats like responsibility, hubris and intelligence therefore excluding Justin Bieber and Kim Kardashian. In most cases, what’s left is fear. Although, on occasion the right candidate can capture the nation’s interest and ride the excitement wave, relying more heavily on charisma and appeal than fear, think John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and most recently Barack Obama. But this phenomenon, if used once, is rarely duplicated for the same individual in a bid for re-election, which is evident in all these cases as well.

In short, political campaigns almost always turn to negative advertising because as the LBJ ad correctly foreshadowed “the stakes are too high” not to do so.